The Performance of Various To-Many Nesting Algorithms – Java, SQL and jOOQ.

It’s been a while since jOOQ 3.15 has been released with its revolutionary standard SQL MULTISET emulation feature. A thing that has been long overdue and which I promised on twitter a few times is to run a few benchmarks comparing the performance of various approaches to nesting to-many relationships with jOOQ.

This article will show, that in some real world scenarios on modest data set sizes, jOOQ’s MULTISET emulation performs about as well as

- manually running single join queries and manually deduplicating results

- manually running multiple queries per nest level and matching results in the client

In contrast, all of the above perform much better than the dreaded N+1 “approach” (or rather, accident), all the while being much more readable and maintainable.

The conclusion is:

- For jOOQ users to freely use

MULTISETwhenever smallish data sets are used (i.e. a nested loop join would be OK, too) - For jOOQ users to use

MULTISETcarefully where large-ish data sets are used (i.e. a hash join or merge join would be better, e.g. in reports) - For ORM vendors to prefer the multiple queries per nest level approach in case they’re in full control of their SQL to materialise predefined object graphs

Benchmark idea

As always, we’re querying the famous Sakila database. There are two types of queries that I’ve tested in this benchmark.

A query that double-nests child collections (DN = DoubleNesting)

The result will be of the form:

record DNCategory (String name) {}

record DNFilm (long id, String title, List<DNCategory> categories) {}

record DNName (String firstName, String lastName) {}

record DNActor (long id, DNName name, List<DNFilm> films) {}

So, the result will be actors and their films and their categories per film. If a single join is being executed, this should cause a lot of duplication in the data (although regrettably, in our test data set, each film only has a single category)

A query that nests two child collections in a single parent (MCC = Multiple Child Collections)

The result will be of the form:

record MCCName (String firstName, String lastName) {}

record MCCActor (long id, MCCName name) {}

record MCCCategory (String name) {}

record MCCFilm (

long id,

String title,

List<MCCActor> actors,

List<MCCCategory> categories

) {}

So, the result will be films and their actors as well as their categories. This is hard to deduplicate with a single join, because of the cartesian product between ACTOR × CATEGORY. But other approaches with multiple queries still work, as well as MULTISET, of course, which will be the most convenient option

Data set size

In addition to the above distinction of use-cases, the benchmark will also try to pull in either:

- The entire data set (we have 1000

FILMentries as well as 200ACTORentries, so not a huge data set), where hash joins tend to be better - Only the subset for either

ACTOR_ID = 1orFILM_ID = 1, respectively, where nested loop joins tend to be better

The expectation here is that a JOIN tends to perform better on larger result sets, because the RDBMS will prefer a hash join algorithm. It’s unlikely the MULTISET emulation can be transformed into a hash join or merge join, given that it uses JSON_ARRAYAGG which might be difficult to transform into something different, which is still equivalent.

Benchmark tests

The following things will be benchmarked for each combination of the above matrix:

- A single

MULTISETquery with its 3 available emulations usingXML(where available),JSON,JSONB - A single

JOINquery that creates a cartesian product between parent and children - An approach that runs 2 queries fetching all the necessary data into client memory, and performs the nesting in the client, thereafter

- A naive N+1 “client side nested loop join,” which is terrible but not unlikely to happen in real world client code, either with jOOQ (less likely, but still possible), or with a lazy loading ORM (more likely, because “accidental”)

The full benchmark logic will be posted at the end of this article.

1. Single MULTISET query (DN)

The query looks like this:

return state.ctx.select(

ACTOR.ACTOR_ID,

// Nested record for the actor name

row(

ACTOR.FIRST_NAME,

ACTOR.LAST_NAME

).mapping(DNName::new),

// First level nested collection for films per actor

multiset(

select(

FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.film().TITLE,

// Second level nested collection for categories per film

multiset(

select(FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_CATEGORY)

.where(FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.eq(FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID))

).convertFrom(r -> r.map(mapping(DNCategory::new)))

)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.where(FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID.eq(ACTOR.ACTOR_ID))

).convertFrom(r -> r.map(mapping(DNFilm::new))))

.from(ACTOR)

// Either fetch all data or filter ACTOR_ID = 1

.where(state.filter ? ACTOR.ACTOR_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.fetch(mapping(DNActor::new));

To learn more about the specific MULTISET syntax and the ad-hoc conversion feature, please refer to earlier blog posts explaining the details. The same is true for the implicit JOIN feature, which I’ll be using in this post to keep SQL a bit more terse.

2. Single JOIN query (DN)

We can do everything with a single join as well. In this example, I’m using a functional style to transform the flat result into the doubly nested collection in a type safe way. It’s a bit quirky, perhaps there are better ways to do this with non-JDK APIs. Since I wouldn’t expect this to be performance relevant, I think it’s good enough:

// The query is straightforward. Just join everything from

// ACTOR -> FILM -> CATEGORY via the relationship tables

return state.ctx.select(

FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().FIRST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().LAST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.film().TITLE,

FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.join(FILM_CATEGORY).on(FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID.eq(FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID))

.where(state.filter ? FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

// Now comes the tricky part. We first use JDK Collectors to group

// results by ACTOR

.collect(groupingBy(

r -> new DNActor(

r.value1(),

new DNName(r.value2(), r.value3()),

// dummy FILM list, we can't easily collect them here, yet

null

),

// For each actor, produce a list of FILM, again with a dummy

// CATEGORY list as we can't collect them here yet

groupingBy(r -> new DNFilm(r.value4(), r.value5(), null))

))

// Set<Entry<DNActor, Map<DNFilm, List<Record6<...>>>>>

.entrySet()

.stream()

// Re-map the DNActor record into itself, but this time, add the

// nested DNFilm list.

.map(a -> new DNActor(

a.getKey().id(),

a.getKey().name(),

a.getValue()

.entrySet()

.stream()

.map(f -> new DNFilm(

f.getKey().id(),

f.getKey().title(),

f.getValue().stream().map(

c -> new DNCategory(c.value6())

).toList()

))

.toList()

))

.toList();

Possibly, this example could be improved to avoid the dummy collection placeholders in the first collect() call, although that would probably require additional record types or structural tuple types like those from jOOλ. I kept it “simple” for this example, though I’ll take your suggestions in the comments.

3. Two queries merged in memory (DN)

A perfectly fine solution is to run multiple queries (but not N+1 queries!), i.e. one query per level of nesting. This isn’t always possible, or optimal, but in this case, there’s a reasonable solution.

I’m spelling out the lengthy Record5<...> types to show the exact types in this blog post. You can use var to profit from type inference, of course. All of these queries use Record.value5() and similar accessors to profit from index based access, just to be fair, preventing the field lookup, which isn’t necessary in the benchmark.

// Straightforward query to get ACTORs and their FILMs

Result<Record5<Long, String, String, Long, String>> actorAndFilms =

state.ctx

.select(

FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().FIRST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().LAST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.film().TITLE)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.where(state.filter ? FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.fetch();

// Create a FILM.FILM_ID => CATEGORY.NAME lookup

// This is just fetching all the films and their categories.

// Optionally, filter for the previous FILM_ID list

Map<Long, List<DNCategory>> categoriesPerFilm = state.ctx

.select(

FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID,

FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_CATEGORY)

.where(state.filter

? FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.in(actorAndFilms.map(r -> r.value4()))

: noCondition())

.collect(intoGroups(

r -> r.value1(),

r -> new DNCategory(r.value2())

));

// Group again by ACTOR and FILM, using the previous dummy

// collection trick

return actorAndFilms

.collect(groupingBy(

r -> new DNActor(

r.value1(),

new DNName(r.value2(), r.value3()),

null

),

groupingBy(r -> new DNFilm(r.value4(), r.value5(), null))

))

.entrySet()

.stream()

// Then replace the dummy collections

.map(a -> new DNActor(

a.getKey().id(),

a.getKey().name(),

a.getValue()

.entrySet()

.stream()

.map(f -> new DNFilm(

f.getKey().id(),

f.getKey().title(),

// And use the CATEGORY per FILM lookup

categoriesPerFilm.get(f.getKey().id())

))

.toList()

))

.toList();

Whew. Unwieldy. Certainly, the MULTISET approach is to be preferred from a readability perspective? All this mapping to intermediary structural data types can be heavy, especially if you make a typo and the compiler trips.

4. N+1 queries (DN)

This naive solution is hopefully not what you’re doing mostly in production, but we’ve all done it at some point (yes, guilty!), so here it is. At least, the logic is more readable than the previous ones, it’s as straightforward as the original MULTISET example, in fact, because it does almost the same thing as the MULTISET example, but instead of doing everything in SQL, it correlates the subqueries in the client:

// Fetch all ACTORs

return state.ctx

.select(ACTOR.ACTOR_ID, ACTOR.FIRST_NAME, ACTOR.LAST_NAME)

.from(ACTOR)

.where(state.filter ? ACTOR.ACTOR_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.fetch(a -> new DNActor(

a.value1(),

new DNName(a.value2(), a.value3()),

// And for each ACTOR, fetch all FILMs

state.ctx

.select(FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID, FILM_ACTOR.film().TITLE)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.where(FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID.eq(a.value1()))

.fetch(f -> new DNFilm(

f.value1(),

f.value2(),

// And for each FILM, fetch all CATEGORY-s

state.ctx

.select(FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_CATEGORY)

.where(FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.eq(f.value1()))

.fetch(r -> new DNCategory(r.value1()))

))

));

1. Single MULTISET query (MCC)

Now, we’ll repeat the exercise again to collect data into a more tree like data structure, where the parent type has multiple child collections, something that is much more difficult to do with JOIN queries. Piece of cake with MULTISET, which nests the collections directly in SQL:

return state.ctx

.select(

FILM.FILM_ID,

FILM.TITLE,

// Get all ACTORs for each FILM

multiset(

select(

FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID,

row(

FILM_ACTOR.actor().FIRST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().LAST_NAME

).mapping(MCCName::new)

)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.where(FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID.eq(FILM.FILM_ID))

).convertFrom(r -> r.map(mapping(MCCActor::new))),

// Get all CATEGORY-s for each FILM

multiset(

select(FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_CATEGORY)

.where(FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.eq(FILM.FILM_ID))

).convertFrom(r -> r.map(mapping(MCCCategory::new))))

.from(FILM)

.where(state.filter ? FILM.FILM_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.fetch(mapping(MCCFilm::new));

Again, to learn more about the specific MULTISET syntax and the ad-hoc conversion feature, please refer to earlier blog posts explaining the details. The same is true for the implicit JOIN feature, which I’ll be using in this post to keep SQL a bit more terse.

2. Single JOIN Query (MCC)

This type of nesting is very hard to do with a single JOIN query, because there will be a cartesian product between ACTOR and CATEGORY, which may be hard to deduplicate after the fact. In this case, it would be possible, because we know that each ACTOR is listed only once per FILM, and so is each CATEGORY. But what if this wasn’t the case? It might not be possible to correctly remove duplicates, because we wouldn’t be able to distinguish:

- Duplicates originating from the

JOINcartesian product - Duplicates originating from the underlying data set

As it is hard (probably not impossible) to guarantee correctness, it is futile to test performance here.

3. Two queries merged in memory (MCC)

This is again quite a reasonable implementation of this kind of nesting using ordinary JOIN queries.

It’s probably what most ORMs do that do not yet support MULTISET like collection nesting. It’s perfectly reasonable to use this approach when the ORM is in full control of the generated queries (e.g. when fetching pre-defined object graphs). But when allowing custom queries, this approach won’t work well for complex queries. For example, JPQL’s JOIN FETCH syntax may use this approach behind the scenes, but this prevents JPQL from supporting non-trivial queries where JOIN FETCH is used in derived tables or correlated subqueries, and itself joins derived tables, etc. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think that seems to be incredibly hard to get right, to transform complex nested queries into multiple individual queries that are executed one after the other, only to then reassemble results.

In any case, it’s an approach that works well for ORMs who are in control of their SQL, but is laborious for end users to implement manually.

// Straightforward query to get ACTORs and their FILMs

Result<Record5<Long, String, Long, String, String>> filmsAndActors =

state.ctx

.select(

FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.film().TITLE,

FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().FIRST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().LAST_NAME)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.where(state.filter ? FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.fetch();

// Create a FILM.FILM_ID => CATEGORY.NAME lookup

// This is just fetching all the films and their categories.

Map<Long, List<MCCCategory>> categoriesPerFilm = state.ctx

.select(

FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID,

FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_CATEGORY)

.where(FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.in(

filmsAndActors.map(r -> r.value1())

))

.and(state.filter ? FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.collect(intoGroups(

r -> r.value1(),

r -> new MCCCategory(r.value2())

));

// Group again by ACTOR and FILM, using the previous dummy

// collection trick

return filmsAndActors

.collect(groupingBy(

r -> new MCCFilm(r.value1(), r.value2(), null, null),

groupingBy(r -> new MCCActor(

r.value3(),

new MCCName(r.value4(), r.value5())

))

))

.entrySet()

.stream()

// This time, the nesting of CATEGORY-s is simpler because

// we don't have to nest them again deeply

.map(f -> new MCCFilm(

f.getKey().id(),

f.getKey().title(),

new ArrayList<>(f.getValue().keySet()),

categoriesPerFilm.get(f.getKey().id())

))

.toList();

As you cam see, it still feels like a chore to do all of this grouping and nesting manually, making sure all the intermediate structural types are correct, but at least the MCC case is a bit simpler than the previous DN case because the nesting is less deep.

But we all know, we’ll eventually combine the approaches and nest tree structures of arbitrary complexity.

4. N+1 queries (MCC)

Again, don’t do this at home (or in production), but we’ve all been there and here’s what a lot of applications do either explicitly (shame on the author!), or implicitly (shame on the ORM for allowing the author to put shame on the author!)

// Fetch all FILMs

return state.ctx

.select(FILM.FILM_ID, FILM.TITLE)

.from(FILM)

.where(state.filter ? FILM.FILM_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.fetch(f -> new MCCFilm(

f.value1(),

f.value2(),

// For each FILM, fetch all ACTORs

state.ctx

.select(

FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().FIRST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().LAST_NAME)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.where(FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID.eq(f.value1()))

.fetch(a -> new MCCActor(

a.value1(),

new MCCName(a.value2(), a.value3())

)),

// For each FILM, fetch also all CATEGORY-s

state.ctx

.select(FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_CATEGORY)

.where(FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.eq(f.value1()))

.fetch(c -> new MCCCategory(c.value1()))

));

Algorithmic complexities

Before we move on to the benchmark results, please be very careful with your interpretation, as always.

The goal of this benchmark wasn’t to find a clear winner (or put shame on a clear loser). The goal of this benchmark was to check if the MULTISET approach has any significant and obvious benefit and/or drawback over the other, more manual and unwieldy approaches.

Don’t conclude that if something is 1.5x or 3x faster than something else, that it is better. It may be in this case, but it may not be in different cases, e.g.

- When the data set is smaller

- When the data set is bigger

- When the data set is distributed differently (e.g. many more categories per film, or a less regular number of films per actor (sakila data sets were generated rather uniformly))

- When switching vendors

- When switching versions

- When you have more load on the system

- When your queries are more diverse (benchmarks tend to run only single queries, which greatly profit from caching in the database server!)

So, again, as with every benchmark result, be very careful with your interpretation.

The N+1 case

Even the N+1 case, which can turn into something terrible isn’t always the wrong choice.

As we know from Big O Notation, problems with bad algorithmic complexities appear only when N is big, not when it is small.

- The algorithmic complexity of a single nested collection is

O(N * log M), i.e.Ntimes looking up values in an index forMvalues (assuming there’s an index) - The algorithmic complexity of a doubly nested collection, however, is much worse, it’s

O(N * log M * ? * log L), i.e.Ntimes looking up values in an index forMvalues, and then?times (depends on the distribution) looking up values in an index forLvalues.

Better hope all of these values are very small. If they are, you’re fine. If they aren’t, you’ll notice in production on a weekend.

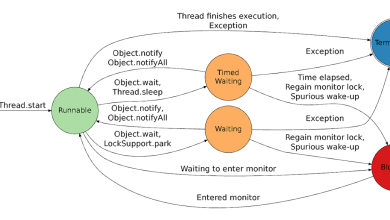

The MULTISET case

While I keep advocating MULTISET as the holy grail because it’s so powerful, convenient, type safe, and reasonably performant, as we’ll see next, it isn’t the holy grail like everything else we ever hoped for promising holy-graily-ness.

While it might be theoretically possible to implement some hash join style nested collection algorithm in the MULTISET case, I suspect that the emulations, which currently use XMLAGG, JSON_ARRAYAGG or similar constructs, won’t be optimised this way, and as such, we’ll get correlated subqueries, which is essentially N+1, but 100% on the server side.

As more and more people use SQL/JSON features, these might be optimised further in the future, though. I wouldn’t hold my breath for RDBMS vendors investing time to improve SQL/XML too much (regrettably).

We can verify the execution plan by running an EXPLAIN (on PostgreSQL) on the query generated by jOOQ for the doubly nested collection case:

explain select

actor.actor_id,

row (actor.first_name, actor.last_name),

(

select coalesce(

json_agg(json_build_array(v0, v1, v2)),

json_build_array()

)

from (

select

film_actor.film_id as v0,

alias_75379701.title as v1,

(

select coalesce(

json_agg(json_build_array(v0)),

json_build_array()

)

from (

select alias_130639425.name as v0

from (

film_category

join category as alias_130639425

on film_category.category_id =

alias_130639425.category_id

)

where film_category.film_id = film_actor.film_id

) as t

) as v2

from (

film_actor

join film as alias_75379701

on film_actor.film_id = alias_75379701.film_id

)

where film_actor.actor_id = actor.actor_id

) as t

)

from actor

where actor.actor_id = 1

The result is:

QUERY PLAN

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Seq Scan on actor (cost=0.00..335.91 rows=1 width=72)

Filter: (actor_id = 1)

SubPlan 2

-> Aggregate (cost=331.40..331.41 rows=1 width=32)

-> Hash Join (cost=5.09..73.73 rows=27 width=23)

Hash Cond: (alias_75379701.film_id = film_actor.film_id)

-> Seq Scan on film alias_75379701 (cost=0.00..66.00 rows=1000 width=23)

-> Hash (cost=4.75..4.75 rows=27 width=8)

-> Index Only Scan using film_actor_pkey on film_actor (cost=0.28..4.75 rows=27 width=8)

Index Cond: (actor_id = actor.actor_id)

SubPlan 1

-> Aggregate (cost=9.53..9.54 rows=1 width=32)

-> Hash Join (cost=8.30..9.52 rows=1 width=7)

Hash Cond: (alias_130639425.category_id = film_category.category_id)

-> Seq Scan on category alias_130639425 (cost=0.00..1.16 rows=16 width=15)

-> Hash (cost=8.29..8.29 rows=1 width=8)

-> Index Only Scan using film_category_pkey on film_category (cost=0.28..8.29 rows=1 width=8)

Index Cond: (film_id = film_actor.film_id)

As expected, two nested scalar subqueries. Don’t get side-tracked by the hash joins inside of the subqueries. Those are expected, because we’re joining between e.g. FILM and FILM_ACTOR, or between CATEGORY and FILM_CATEGORY in the subquery. But this doesn’t affect how the two subqueries are correlated to the outer-most query, where we cannot use any hash joins.

So, we have an N+1 situation, just without the latency of running a server roundtrip every time! The algorithmic complexity is the same, but the constant overhead per item has been removed, allowing for bigger N before it hurts – still the approach will fail eventually, just like having too many JOIN on large data sets is inefficient in RDBMS that do not support hash join or merge join, but only nested loop join (e.g. older MySQL versions).

Future versions of jOOQ may support MULTISET more natively on Oracle and PostgreSQL. It’s already supported natively in Informix, which has standard SQL MULTISET support. In PostgreSQL, things could be done using ARRAY(<subquery>) and ARRAY_AGG(), which might be more transparent to the optimiser than JSON_AGG. If it is, I’ll definitely follow up with another blog post.

The single JOIN query case

I would expect this approach to work OK-ish, if the nested collections aren’t too big (i.e. there isn’t too much duplicate data). Once the nested collections grow bigger, the deduplication will bear quite some costs as:

- More redundant data has to be produced on the server side (requiring more memory and CPU)

- More redundant data has to be transferred over the wire

- More deduplication needs to be done on the client side (requiring more memory and CPU)

All in all, this approach seems silly for complex nesting, but doable for a single nested collection. This benchmark doesn’t test huge deduplications.

The 1-query-per-nest-level case

I would expect the very unwieldy 1-query-per-nest-level case to be the most performant as N scales. It’s also relatively straightforward for an ORM to implement, in case the ORM is in full control of the generated SQL and doesn’t have to respect any user query requirements. It won’t work well if mixed into user query syntax, and it’s hard to do for users manually every time.

However, it’s an “after-the-fact” collection nesting approach, meaning that it only works well if some assumptions about the original query can be maintained. E.g. JOIN FETCH in JPQL only takes you this far. It may have been an OK workaround to nesting collections and making the concept available for simple cases, but I’m positive JPA / JPQL will evolve and also adopt MULTISET based approaches. After all, MULTISET has been a SQL standard for ORDBMS for ages now.

The long-term solution for nesting collections can only be to nest them directly in SQL, and make all the logic available to the optimiser for its various decisions.

Benchmark results

Finally, some results! I’ve run the benchmark on these 4 RDBMS:

- MySQL

- Oracle

- PostgreSQL

- SQL Server

I didn’t run it on Db2, which can’t correlate derived tables yet, an essential feature for correlated MULTISET subqueries in jOOQ in 3.15 – 3.17’s MULTISET emulation (see https://github.com/jOOQ/jOOQ/issues/12045 for details).

As always, since benchmark results cannot be published for commercial RDBMS, I’m not publishing actual times, only relative times, where the slowest execution is 1, and faster executions are multiples of 1. Imagine some actual unit of measurement, like operations/second, only it’s not per second but per undisclosed unit of time. That way, the RDBMS can only be compared with themselves, not with each other.

MySQL:

Benchmark (filter) Mode Cnt Score Error Units

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingJoin true thrpt 7 4413.48 ± 448.63 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSON true thrpt 7 2524.96 ± 402.38 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSONB true thrpt 7 2738.62 ± 332.37 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingNPlusOneQueries true thrpt 7 265.37 ± 42.98 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingTwoQueries true thrpt 7 2256.38 ± 363.18 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingJoin false thrpt 7 266.27 ± 13.31 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSON false thrpt 7 54.98 ± 2.25 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSONB false thrpt 7 54.05 ± 1.58 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingNPlusOneQueries false thrpt 7 1.00 ± 0.11 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingTwoQueries false thrpt 7 306.23 ± 11.64 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSON true thrpt 7 3058.68 ± 722.24 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSONB true thrpt 7 3179.18 ± 333.77 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsNPlusOneQueries true thrpt 7 1845.75 ± 167.26 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsTwoQueries true thrpt 7 2425.76 ± 579.73 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSON false thrpt 7 91.78 ± 2.65 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSONB false thrpt 7 92.48 ± 2.25 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsNPlusOneQueries false thrpt 7 2.84 ± 0.48 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsTwoQueries false thrpt 7 171.66 ± 19.8 ops/time-unit

Oracle:

Benchmark (filter) Mode Cnt Score Error Units

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingJoin true thrpt 7 669.54 ± 28.35 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSON true thrpt 7 419.13 ± 23.60 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSONB true thrpt 7 432.40 ± 17.76 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetXML true thrpt 7 351.42 ± 18.70 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingNPlusOneQueries true thrpt 7 251.73 ± 30.19 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingTwoQueries true thrpt 7 548.80 ± 117.40 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingJoin false thrpt 7 15.59 ± 1.86 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSON false thrpt 7 2.41 ± 0.07 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSONB false thrpt 7 2.40 ± 0.07 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetXML false thrpt 7 1.91 ± 0.06 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingNPlusOneQueries false thrpt 7 1.00 ± 0.12 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingTwoQueries false thrpt 7 13.63 ± 1.57 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSON true thrpt 7 1217.79 ± 89.87 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSONB true thrpt 7 1214.07 ± 76.10 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetXML true thrpt 7 702.11 ± 87.37 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsNPlusOneQueries true thrpt 7 919.47 ± 340.63 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsTwoQueries true thrpt 7 1194.05 ± 179.92 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSON false thrpt 7 2.89 ± 0.08 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSONB false thrpt 7 3.00 ± 0.05 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetXML false thrpt 7 1.04 ± 0.17 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsNPlusOneQueries false thrpt 7 1.52 ± 0.08 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsTwoQueries false thrpt 7 13.00 ± 1.96 ops/time-unit

PostgreSQL:

Benchmark (filter) Mode Cnt Score Error Units

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingJoin true thrpt 7 4128.21 ± 398.82 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSON true thrpt 7 3187.88 ± 409.30 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSONB true thrpt 7 3064.69 ± 154.75 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetXML true thrpt 7 1973.44 ± 166.22 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingNPlusOneQueries true thrpt 7 267.15 ± 34.01 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingTwoQueries true thrpt 7 2081.03 ± 317.95 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingJoin false thrpt 7 275.95 ± 6.80 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSON false thrpt 7 53.94 ± 1.06 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSONB false thrpt 7 45.00 ± 0.52 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetXML false thrpt 7 25.11 ± 1.01 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingNPlusOneQueries false thrpt 7 1.00 ± 0.07 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingTwoQueries false thrpt 7 306.11 ± 35.40 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSON true thrpt 7 4710.47 ± 194.37 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSONB true thrpt 7 4391.78 ± 223.62 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetXML true thrpt 7 2740.73 ± 186.70 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsNPlusOneQueries true thrpt 7 1792.94 ± 134.50 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsTwoQueries true thrpt 7 2821.82 ± 252.34 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSON false thrpt 7 68.45 ± 2.58 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSONB false thrpt 7 58.59 ± 0.58 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetXML false thrpt 7 15.58 ± 0.35 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsNPlusOneQueries false thrpt 7 2.71 ± 0.16 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsTwoQueries false thrpt 7 163.03 ± 7.54 ops/time-unit

SQL Server:

Benchmark (filter) Mode Cnt Score Error Units

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingJoin true thrpt 7 4081.85 ± 1029.84 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSON true thrpt 7 1243.17 ± 84.24 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSONB true thrpt 7 1254.13 ± 56.94 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetXML true thrpt 7 1077.23 ± 61.50 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingNPlusOneQueries true thrpt 7 264.45 ± 16.12 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingTwoQueries true thrpt 7 1608.92 ± 145.75 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingJoin false thrpt 7 359.08 ± 20.88 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSON false thrpt 7 8.41 ± 0.06 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetJSONB false thrpt 7 8.32 ± 0.15 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingMultisetXML false thrpt 7 7.24 ± 0.08 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingNPlusOneQueries false thrpt 7 1.00 ± 0.09 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.doubleNestingTwoQueries false thrpt 7 376.02 ± 7.60 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSON true thrpt 7 1735.23 ± 178.30 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSONB true thrpt 7 1736.01 ± 92.26 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetXML true thrpt 7 1339.68 ± 137.47 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsNPlusOneQueries true thrpt 7 1264.50 ± 343.56 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsTwoQueries true thrpt 7 1057.54 ± 130.13 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSON false thrpt 7 7.90 ± 0.05 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSONB false thrpt 7 7.85 ± 0.15 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsMultisetXML false thrpt 7 5.06 ± 0.18 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsNPlusOneQueries false thrpt 7 1.77 ± 0.28 ops/time-unit

MultisetVsJoinBenchmark.multipleChildCollectionsTwoQueries false thrpt 7 255.08 ± 19.22 ops/time-unit

Benchmark conclusion

As can be seen in most RDBMS:

- All RDBMS produced similar results.

- The added latency of N+1 almost always contributed a significant performance penalty. An exception is where we have a

filter = trueand multiple child collections, in case of which the parentNis 1 (duh) and only a single nest level is implemented. MULTISETperformed even better than the single queryJOINbased approach or the 1-query-per-nest-level approach whenfilter = trueand with multiple child collections, probably because of the more compact data format.- The

XMLbasedMULTISETemulation is always the slowest among the emulations, likely because it requires more formatting. (In one Oracle case, theXMLbasedMULTISETemulation was even slower than the ordinary N+1 approach). JSONBis a bit slower in PostgreSQL thanJSON, likely becauseJSONis a purely text based format, without any post processing / cleanup.JSONB‘s advantage is not with projection-only queries, but with storage, comparison, and other operations. For most usages,JSONBis probably better. For projection only,JSONis better (jOOQ 3.17 will make this the default for theMULTISETemulation)- It’s worth noting that jOOQ serialises records as JSON arrays, not JSON objects, in order to avoid transferring repetitive column names, and offer positional index when deserialising the array.

- For large-ish data sets (where

filter = false), the N+1 factor of aMULTISETcorrelated subquery can become a problem (due to the nature of algorithmic complexity), as it prevents using more efficient hash joins. In these cases, the single queryJOINbased approach or 1-query-per-nest-level approach are better

In short:

MULTISETcan be used whenever a nested loop join is optimal.- If a hash join or merge join would be more optimal, then the single query

JOINapproach or the 1-query-per-nest-level approach tend to perform better (though they have their own caveats as complexity grows)

The benefit in convenience and correctness is definitely worth it for small data sets. For larger data sets, continue using JOIN. As always, there’s no silver bullet.

Things this blog post did not investigate

A few things weren’t investigated by this blog post, including:

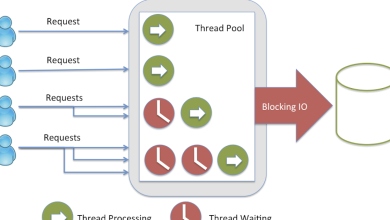

- The serialisation overhead in the server. Ordinary JDBC

ResultSettend to profit from a binary network protocol between server and client. WithJSONorXML, that benefit of protocol compactness goes away, and a systematic overhead is produced. To what extent this plays a role has not been investigated. - The same is true on the client side, where nested

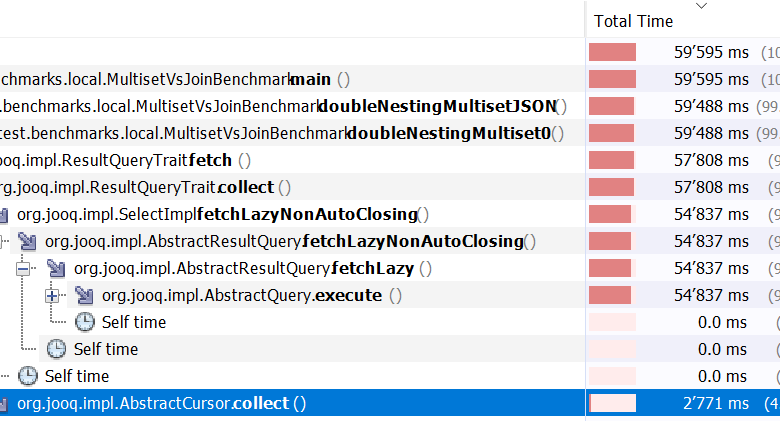

JSONorXMLdocuments need to be deserialised. While the following VisualVM screenshot shows that there is some overhead, it is not significant compared to the execution time. Also, it isn’t a significant amount more overhead than what jOOQ already produces when mapping betweenResultSetand jOOQ data structures. I mean, obviously, using JDBC directly can be faster if you’re doing it right, but then you remove all the convenience jOOQ creates.

Benchmark code

Finally, should you wish to reproduce this benchmark, or adapt it to your own needs, here’s the code.

I’ve used JMH for the benchmark. While this is obviously not a “micro benchmark,” I like JMH’s approach to benchmarking, including:

- Easy configuration

- Warmup penalty is removed by doing warmup iterations

- Statistics are collected to handle outlier effects

Obviously, all the version use jOOQ for query building, execution, mapping, to achieve fair and meaningful results. It would be possible to use JDBC directly in the non-MULTISET approaches, but that wouldn’t be a fair comparison of concepts.

The benchmark assumes availability of a SAKILA database instance, as well as generated code, similar to this jOOQ demo.

package org.jooq.test.benchmarks.local;

import static java.util.stream.Collectors.groupingBy;

import static org.jooq.Records.intoGroups;

import static org.jooq.Records.mapping;

import static org.jooq.example.db.postgres.Tables.*;

import static org.jooq.impl.DSL.multiset;

import static org.jooq.impl.DSL.noCondition;

import static org.jooq.impl.DSL.row;

import static org.jooq.impl.DSL.select;

import java.io.InputStream;

import java.sql.Connection;

import java.sql.DriverManager;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.Properties;

import java.util.function.Consumer;

import org.jooq.DSLContext;

import org.jooq.Record5;

import org.jooq.Result;

import org.jooq.conf.NestedCollectionEmulation;

import org.jooq.conf.Settings;

import org.jooq.impl.DSL;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Benchmark;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Fork;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Level;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Measurement;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Param;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Scope;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Setup;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.State;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.TearDown;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Warmup;

@Fork(value = 1)

@Warmup(iterations = 3, time = 3)

@Measurement(iterations = 7, time = 3)

public class MultisetVsJoinBenchmark {

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

public static class BenchmarkState {

Connection connection;

DSLContext ctx;

@Param({ "true", "false" })

boolean filter;

@Setup(Level.Trial)

public void setup() throws Exception {

try (InputStream is = BenchmarkState.class.getResourceAsStream("/config.mysql.properties")) {

Properties p = new Properties();

p.load(is);

Class.forName(p.getProperty("db.mysql.driver"));

connection = DriverManager.getConnection(

p.getProperty("db.mysql.url"),

p.getProperty("db.mysql.username"),

p.getProperty("db.mysql.password")

);

}

ctx = DSL.using(connection, new Settings()

.withExecuteLogging(false)

.withRenderSchema(false));

}

@TearDown(Level.Trial)

public void teardown() throws Exception {

connection.close();

}

}

record DNName(String firstName, String lastName) {}

record DNCategory(String name) {}

record DNFilm(long id, String title, List<DNCategory> categories) {}

record DNActor(long id, DNName name, List<DNFilm> films) {}

@Benchmark

public List<DNActor> doubleNestingMultisetXML(BenchmarkState state) {

state.ctx.settings().setEmulateMultiset(NestedCollectionEmulation.XML);

return doubleNestingMultiset0(state);

}

@Benchmark

public List<DNActor> doubleNestingMultisetJSON(BenchmarkState state) {

state.ctx.settings().setEmulateMultiset(NestedCollectionEmulation.JSON);

return doubleNestingMultiset0(state);

}

@Benchmark

public List<DNActor> doubleNestingMultisetJSONB(BenchmarkState state) {

state.ctx.settings().setEmulateMultiset(NestedCollectionEmulation.JSONB);

return doubleNestingMultiset0(state);

}

private List<DNActor> doubleNestingMultiset0(BenchmarkState state) {

return state.ctx

.select(

ACTOR.ACTOR_ID,

row(

ACTOR.FIRST_NAME,

ACTOR.LAST_NAME

).mapping(DNName::new),

multiset(

select(

FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.film().TITLE,

multiset(

select(FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_CATEGORY)

.where(FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.eq(FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID))

).convertFrom(r -> r.map(mapping(DNCategory::new)))

)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.where(FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID.eq(ACTOR.ACTOR_ID))

).convertFrom(r -> r.map(mapping(DNFilm::new))))

.from(ACTOR)

.where(state.filter ? ACTOR.ACTOR_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.fetch(mapping(DNActor::new));

}

@Benchmark

public List<DNActor> doubleNestingJoin(BenchmarkState state) {

return state.ctx

.select(

FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().FIRST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().LAST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.film().TITLE,

FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.join(FILM_CATEGORY).on(FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID.eq(FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID))

.where(state.filter ? FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.collect(groupingBy(

r -> new DNActor(r.value1(), new DNName(r.value2(), r.value3()), null),

groupingBy(r -> new DNFilm(r.value4(), r.value5(), null))

))

.entrySet()

.stream()

.map(a -> new DNActor(

a.getKey().id(),

a.getKey().name(),

a.getValue()

.entrySet()

.stream()

.map(f -> new DNFilm(

f.getKey().id(),

f.getKey().title(),

f.getValue().stream().map(c -> new DNCategory(c.value6())).toList()

))

.toList()

))

.toList();

}

@Benchmark

public List<DNActor> doubleNestingTwoQueries(BenchmarkState state) {

Result<Record5<Long, String, String, Long, String>> actorAndFilms = state.ctx

.select(

FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().FIRST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().LAST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.film().TITLE)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.where(state.filter ? FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.fetch();

Map<Long, List<DNCategory>> categoriesPerFilm = state.ctx

.select(

FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID,

FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_CATEGORY)

.where(state.filter

? FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.in(actorAndFilms.map(r -> r.value4()))

: noCondition())

.collect(intoGroups(

r -> r.value1(),

r -> new DNCategory(r.value2())

));

return actorAndFilms

.collect(groupingBy(

r -> new DNActor(r.value1(), new DNName(r.value2(), r.value3()), null),

groupingBy(r -> new DNFilm(r.value4(), r.value5(), null))

))

.entrySet()

.stream()

.map(a -> new DNActor(

a.getKey().id(),

a.getKey().name(),

a.getValue()

.entrySet()

.stream()

.map(f -> new DNFilm(

f.getKey().id(),

f.getKey().title(),

categoriesPerFilm.get(f.getKey().id())

))

.toList()

))

.toList();

}

@Benchmark

public List<DNActor> doubleNestingNPlusOneQueries(BenchmarkState state) {

return state.ctx

.select(ACTOR.ACTOR_ID, ACTOR.FIRST_NAME, ACTOR.LAST_NAME)

.from(ACTOR)

.where(state.filter ? ACTOR.ACTOR_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.fetch(a -> new DNActor(

a.value1(),

new DNName(a.value2(), a.value3()),

state.ctx

.select(FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID, FILM_ACTOR.film().TITLE)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.where(FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID.eq(a.value1()))

.fetch(f -> new DNFilm(

f.value1(),

f.value2(),

state.ctx

.select(FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_CATEGORY)

.where(FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.eq(f.value1()))

.fetch(r -> new DNCategory(r.value1()))

))

));

}

record MCCName(String firstName, String lastName) {}

record MCCCategory(String name) {}

record MCCActor(long id, MCCName name) {}

record MCCFilm(long id, String title, List<MCCActor> actors, List<MCCCategory> categories) {}

@Benchmark

public List<MCCFilm> multipleChildCollectionsMultisetXML(BenchmarkState state) {

state.ctx.settings().setEmulateMultiset(NestedCollectionEmulation.XML);

return multipleChildCollectionsMultiset0(state);

}

@Benchmark

public List<MCCFilm> multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSON(BenchmarkState state) {

state.ctx.settings().setEmulateMultiset(NestedCollectionEmulation.JSON);

return multipleChildCollectionsMultiset0(state);

}

@Benchmark

public List<MCCFilm> multipleChildCollectionsMultisetJSONB(BenchmarkState state) {

state.ctx.settings().setEmulateMultiset(NestedCollectionEmulation.JSONB);

return multipleChildCollectionsMultiset0(state);

}

private List<MCCFilm> multipleChildCollectionsMultiset0(BenchmarkState state) {

return state.ctx

.select(

FILM.FILM_ID,

FILM.TITLE,

multiset(

select(

FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID,

row(

FILM_ACTOR.actor().FIRST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().LAST_NAME

).mapping(MCCName::new)

)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.where(FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID.eq(FILM.FILM_ID))

).convertFrom(r -> r.map(mapping(MCCActor::new))),

multiset(

select(

FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME

)

.from(FILM_CATEGORY)

.where(FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.eq(FILM.FILM_ID))

).convertFrom(r -> r.map(mapping(MCCCategory::new))))

.from(FILM)

.where(state.filter ? FILM.FILM_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.fetch(mapping(MCCFilm::new));

}

@Benchmark

public List<MCCFilm> multipleChildCollectionsTwoQueries(BenchmarkState state) {

Result<Record5<Long, String, Long, String, String>> filmsAndActors = state.ctx

.select(

FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.film().TITLE,

FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().FIRST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().LAST_NAME)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.where(state.filter ? FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.fetch();

Map<Long, List<MCCCategory>> categoriesPerFilm = state.ctx

.select(

FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID,

FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_CATEGORY)

.where(FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.in(

filmsAndActors.map(r -> r.value1())

))

.and(state.filter ? FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.collect(intoGroups(

r -> r.value1(),

r -> new MCCCategory(r.value2())

));

return filmsAndActors

.collect(groupingBy(

r -> new MCCFilm(r.value1(), r.value2(), null, null),

groupingBy(r -> new MCCActor(r.value3(), new MCCName(r.value4(), r.value5())))

))

.entrySet()

.stream()

.map(f -> new MCCFilm(

f.getKey().id(),

f.getKey().title(),

new ArrayList<>(f.getValue().keySet()),

categoriesPerFilm.get(f.getKey().id())

))

.toList();

}

@Benchmark

public List<MCCFilm> multipleChildCollectionsNPlusOneQueries(BenchmarkState state) {

return state.ctx

.select(FILM.FILM_ID, FILM.TITLE)

.from(FILM)

.where(state.filter ? FILM.FILM_ID.eq(1L) : noCondition())

.fetch(f -> new MCCFilm(

f.value1(),

f.value2(),

state.ctx

.select(

FILM_ACTOR.ACTOR_ID,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().FIRST_NAME,

FILM_ACTOR.actor().LAST_NAME)

.from(FILM_ACTOR)

.where(FILM_ACTOR.FILM_ID.eq(f.value1()))

.fetch(a -> new MCCActor(

a.value1(),

new MCCName(a.value2(), a.value3())

)),

state.ctx

.select(FILM_CATEGORY.category().NAME)

.from(FILM_CATEGORY)

.where(FILM_CATEGORY.FILM_ID.eq(f.value1()))

.fetch(c -> new MCCCategory(c.value1()))

));

}

}