Musical Clocks and Organs – Communications of the ACM

Many clocks contain musical mechanisms: table clocks, standing clocks, longcase clocks, flute-playing clocks, and pocket watches. Automaton figures, furniture (e.g. desks), jewelry, as well as picture clocks sometimes also have built-in musical mechanisms.

For the musical program, historical systems used different sound recording media: pinned cylinder, perforated disc, perforated cardboard tape, and perforated paper roll were widely used. Many mechanical musical instruments function as if by magic, and some have a pedal. With the emergence of the phonograph record and the gramophone, punched paper and cardboard tapes, brass cylinders, cardboard, and sheet metal discs disappeared as sound recording media.

Several classical composers wrote music for mechanical musical instruments, including Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, George Frideric Händel, Franz Joseph Haydn, Leopold Mozart, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Mechanical musical instruments were mainly made in Germany, France, and Switzerland. Clockmakers were often involved. There are well-known museums of musical automatons in Germany (Bruchsal) and Switzerland (Seewen), for example. Mechanical musical instruments can also be found in technical and art museums.

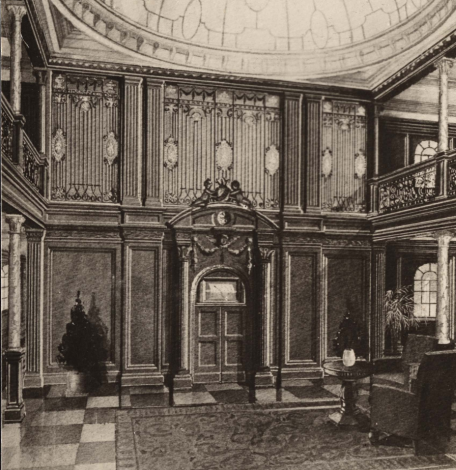

On the Britannic, the sister ship of the “unsinkable” Titanic, there was a huge philharmonic organ (see Figs. 1–3). The organ, which was lost for a long time, is now in Seewen in Switzerland.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Credit: Museum für Musikautomaten, Seewen SO

Credit: Museum für Musikautomaten, Seewen SO

The Mortier organs (see Figure 4) are also quite impressive.

Credit: Museum für Musikautomaten, Seewen SO

This post is part of a series that presents selected technical marvels from the fields of computing technology, mathematics, astronomy, surveying, time measurement, looms, and automatons (automaton figures, chess-playing machines, musical automatons, automaton writers, drawing automatons, automaton clocks, picture clocks, globes, and historical robots). The examples are largely from the 15th to 20th centuries and do not claim to be exhaustive. In particular, artifacts are included for which high-quality illustrations are available. Most of the objects come from Europe, with a few from Africa, America, Asia, and Australia. The order is predominantly chronological. Famous names such as Archimedes, Hipparchus, Heron of Alexandria, Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo Galilei, John Napier, Jost Bürgi, Blaise Pascal, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and Charles Babbage are associated with these works. In some cases, however, the inventors are unknown (e.g. abacus, Antikythera Mechanism, yupana, quipu); see Technical Marvels, Part 5: Chess Automatons – Communications of the ACM

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the museums, especially the Museum für Musikautomaten in Seewen, Switzerland, for providing high-quality photos.

References

This post is based on:

Bruderer, Herbert: Meilensteine der Rechentechnik, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, Berlin/Boston, 3rd edition 2020, volume 1, 970 pages, 577 figures, 114 tables, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110669664

Bruderer, Herbert: Meilensteine der Rechentechnik, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, Berlin/Boston, 3rd edition 2020, volume 2, 1055 pages, 138 figures, 37 tables, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110669671

Bruderer, Herbert: Milestones in Analog and Digital Computing, Springer Nature Switzerland AG, Cham, 3rd edition 2020, 2 volumes, 2113 pages, 715 illustrations, 151 tables, translated from the German by Dr John McMinn, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40974-6

Herbert Bruderer is a retired lecturer in the Department of Computer Science at ETH Zurich and a historian of technology. He recently was added to the Honor Roll of the IT History Society.